Het kunstwerk

Carasso created the National Monument for the Merchant Navy in memory of the victims who died at sea during the Second World War. The statue is 46 metres high, and is entitled De Boeg (‘The Bow’). The sculpture is a stylised ship’s bow, ‘cutting’ through concrete waves. The piece was unveiled in 1957, and even before the unveiling, the sculpture was the object of criticism; the decision was later made to add a human element to the work. In 1965, a group of bronze figures were placed at the foot of the statue. The text ‘Zij hielden koers (they stayed on course)’ appears at the base of the monument.

A pastel drawing made around 1950 was a first study for De Boeg. It shows an abstract image in which various angular and round shapes are piled up on top of and piercing one another. An elongated triangle towers out above the image. In this work, the sculpture appears to be a playful collage of shapes, evoking associations of a ship here and there, for example, a bow, waves and a steam pipe. Carasso sketched the image on the quay; one of the bridges over the Maas River comes ashore under the statue.

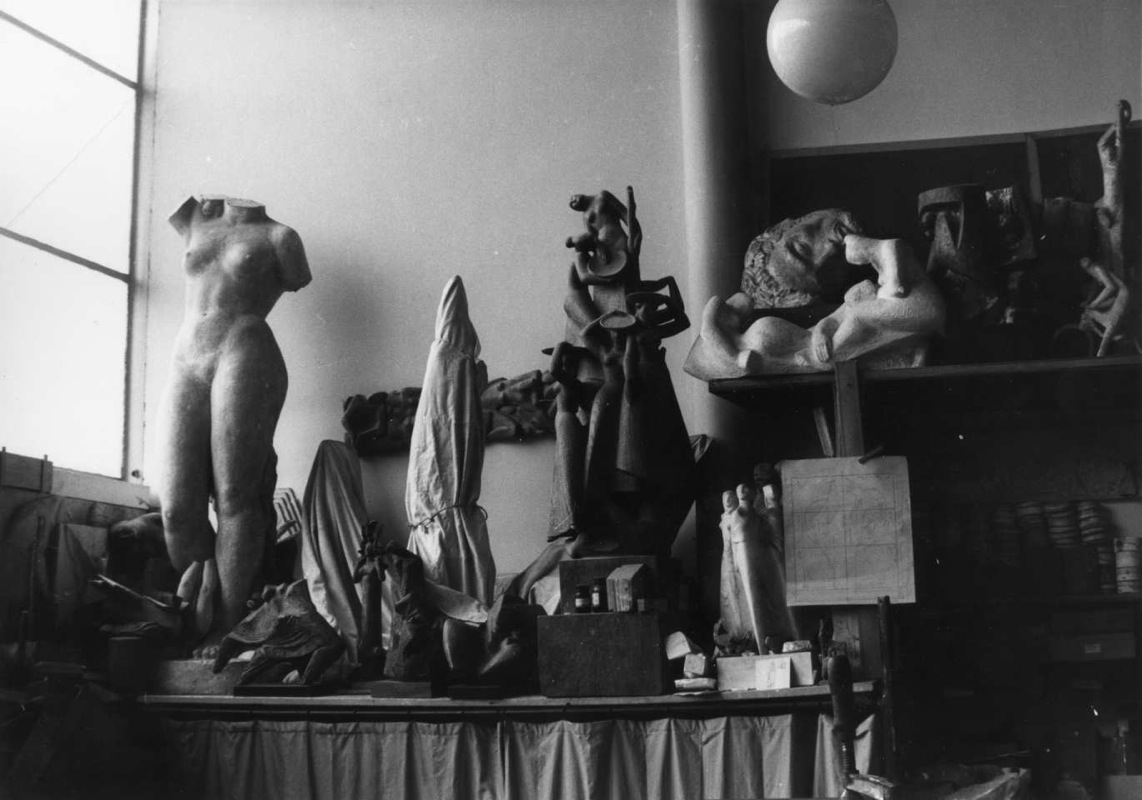

The final design was created in 1956; a wooden sculpture 230 cm high, covered with metal tape. The model was sold at an auction in 2005 by the Historical Museum, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, and the Maritime Museum in Rotterdam for 18,000 Euros. This sculpture is much sleeker and simpler in shape than the initial study. It was then executed according to the design, and De Boeg was unveiled on the quay of the Leuvenhaven in 1957. Like the bow of a ship, an aluminium column rises 46 metres high, towering over the angular concrete waves. The sculpture has much harder lines than the study created in the early 1950s. It is primarily a portrayal of the perseverance and drive of the mariners.

Even before it was unveiled, the sculpture was the subject of a great deal of discussion. The National Monument for the Merchant Navy foundation asked Carasso to ‘make the human element more prevalent’. It would be some time before the foundation and the artist were able to agree on the form this human element should take. It wasn’t until 1965 that the group of figures were placed at the foot of the monument. The group is made up of a helmsman, three mariners, and a drowned man, all of whom are tied to one another and to part of the ship by a rope. Huddled together, they fight against the water. Next to the high waves and the bow towering over them, the figures still appear rather diminutive.