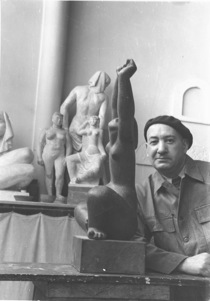

Frederico Carasso

In 1947, he was asked to design a sculpture for the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam, in memory of the fallen athletes. It was an enormous figure of a man holding a torch, and was entitled ‘Prometheus’. At the time, this huge sculpture was the largest in the Netherlands. Various monuments to the resistance followed, for the Municipality of Dreumel, Philips in Eindhoven, and the Municipality of Sprang-Kapelle. In 1953, a second commission from Philips followed; a sun dial which aimed to depict the company’s growth and progress. In the early 1950s, the contest to design the National Monument for the Merchant Navy was held, and Carasso ultimately placed as one of the winners. Although he was not chosen as the first place winner by the judges, his design received the most applause from the press and the general public. Not long after this, a retrospective of his work was shown at the Rotterdamsche Kunstkring (Rotterdam Art Society) in 1953.

At the time, Italian sculpture was gaining in popularity, and Carasso wrote several articles about it in De Kroniek and Apollo. Commissioned by the NKB, he travelled to Italy to establish contacts and study the possibility of an exchange programme. In 1954, he wrote the foreword for the Mostra exhibition at the Rotterdamsche Kunstkring, which was dedicated exclusively to Italian art. In 1958, he was one of the judges at the Sonsbeek exhibition where he was responsible for the selection of Italian works. He did not appreciate the developments within the world of sculpture without reservations, however. In 1953, with his article ‘De knuppel in het Hoenderhok‘; published in De Kroniek he discussed the increasing conflict between realism and abstraction in sculpture. His commentary on the work of artists such as Ossip Zadkine was not appreciated. In spite of his objections to abstract art, his own work became less realistic during the 1950s. Figures became more stylised and angular. The subject, however, always remained recognisable. During the 1960s, his work once again became more realistic, and the shapes were more rounded.

Carasso is primarily known as being a sculptor. In addition, he also created works on paper, in a variety of styles and techniques. These works vary from colourful and cheerful gouaches to darker pastel drawings, pen and ink drawings and collages. The subjects range from illustrations to cartoons. The collages and pen and ink drawings in particular are sometimes absurd and mocking in tone. The oppression by Fascism and colonialism are topics which also appear frequently. In 1956, Carasso was appointed as a professor of sculpture at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht as the successor to Oscar Jespers. In spite of the fact that he was no longer a member of the vanguard, he still remained a successful sculptor with plenty of commissions and exhibitions. Carasso died in Amsterdam in 1969.